Anisha Ahmed – Lead Practitioner of English and Curriculum Leader

When we ask our students to write for an extended period of time, we can often be met with defeated faces, sullen sighs and the occasional (and sometimes dramatic) head on table. Sometimes, as practitioners, we might not understand why. But, if we consider that when asking our students to ‘write’ we really are expecting them to coordinate multiple different processes simultaneously, it’s no wonder some of our pupils can find this a challenging task.

Writing is, in fact, the hardest thing we ask our students to do (Hochman and Wexler, 2017) but when we get it right we know that we are providing them with the most powerful tool. Extended writing gives our pupils the opportunity to engage in deep concepts, think critically, and express themselves in a sophisticated way.

For these reasons, it really is important that we help our students master the process of extended writing and understand that it needs to be taught, not tested (Turner, 2021). In this blog, I will be sharing 5 practical strategies that have allowed me to empower my students in their writing tasks.

- Give them a purpose:

What are they writing and why?

It’s likely that when asking a student these questions their responses might be “I am writing a paragraph”, “I’m writing a 12 marker” or “because I need to do this for an assessment”. Whilst these answers aren’t technically ‘wrong’ they fail to capture the essence of the multi-structural skills we are asking them to develop and, in turn, can be a little demotivating. We can help them with this by providing them a purpose that goes far beyond the criteria of an exam question.

Big Question:

Provide students a ‘big question’ (stolen from the amazing work of Stuart Pryke and Matt Lynch) which they will later be asked to write about. This allows them to thoughtfully consider a concept, theme or idea and approach their writing task in a more purposeful way. Give this to students at the start of the lesson so that they are already encouraged to think deeply and are able to develop good ideas as they go; this also means they are less likely to view the written work as an isolated task.

For example:

“Today we will write a paragraph about Lady Macbeth in Act 5”, becomes, “our Big Question is: What becomes of Lady Macbeth in Act 5?”.

In this example students are already considering and formulating ideas, and understand that a big part of the writing task is an exploration of key themes and concepts.

- Planning through Oracy

There are some students who we believe can ‘verbalise their ideas articulately’ but perhaps struggle to write in the same way. This is not necessarily a bad thing and we should play on these students’ strengths; engaging in oracy tasks can support students’ vocabulary acquisition and overall expression.

Give students the opportunity to rehearse the content of their writing task by making it an enjoyable discussion. Provide students with oracy specific interventions which allow them to formulate and build on their ideas, in a more formal and sophisticated way, which will later strengthen the quality of their writing. You can find lots of great oracy strategies in the SB Oracy Toolkit!

- Explicit Writing Instruction: Sentence Level

Students need explicit instruction of writing to be able to confidently pursue writing tasks independently. As teachers, we do this in multiple ways, including: modelling the writing process, providing high quality worked examples and joint construction. We must remember, though, that sentences are the building blocks of writing and ‘The Writing Revolution’, recommended to me by two colleagues, has really helped ‘revolutionise’ my practice of this.

Select one sentence level focus for your students and ensure that they have ample opportunities to practice these sentence level writing tasks before moving on to the next one. Recently, I have been working on ‘because, but, so’, expanded sentences and Janus-faced transitions to ensure my students’ are developing and building on their ideas, in an articulate way.

- Time and practice

Too often, we feel the need to rush the time given on writing tasks as we want to make sure we have moved on to the next task. If we want our students to write an ‘extended’ amount, however, and of good quality, we must give them the time. As we see our students 4x a week, in English we have been embedding a 3:1 split in our curriculum in which 1 lesson per week is dedicated to extended writing practice.

This might not be possible for other subject areas, but it’s important to think about ways in which writing tasks can be embedded into the content of the curriculum and that we are giving students sufficient time and scaffold to perfect their skills.

- Feedback

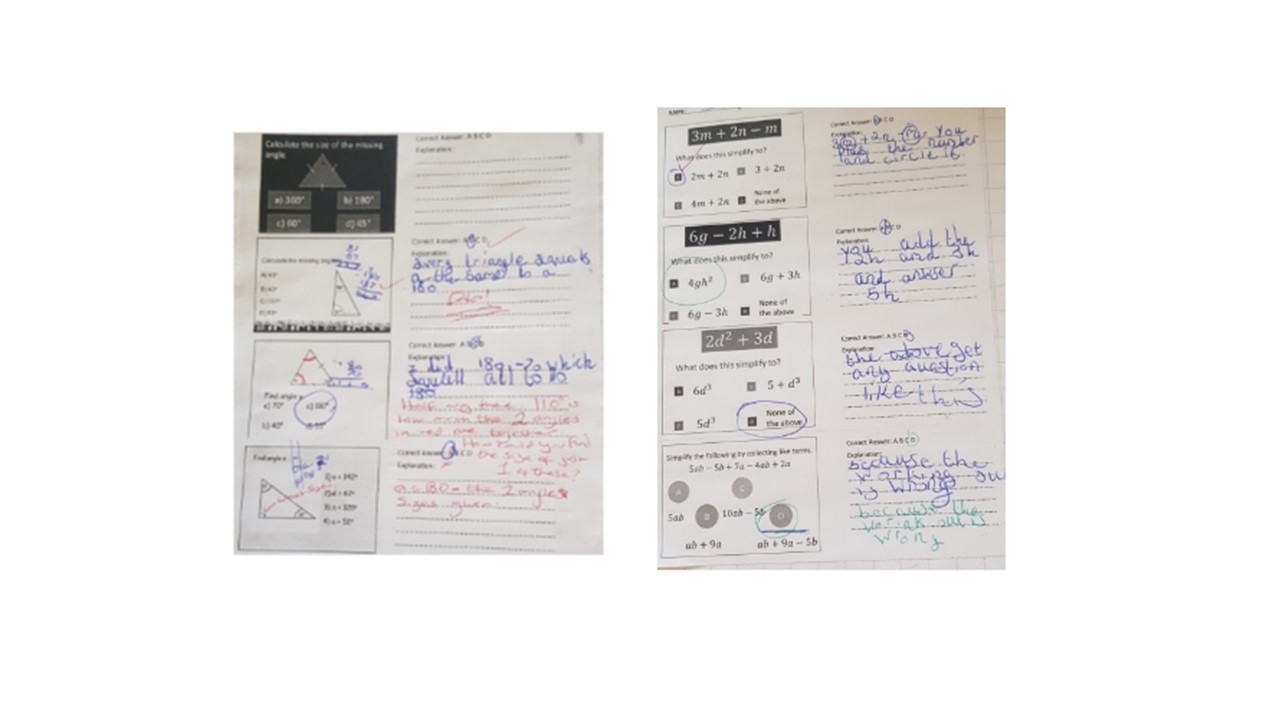

Lastly, but most importantly, students need to review their work to understand how to edit and improve their writing. This can, of course, include: self and peer feedback, teacher marking and, in relation to the previous strategy on sentence level instruction, specific zoomed in feedback.

For example, when focussing on asking students to build on their ideas using janus-faced transitions, I asked students to highlight their independent use of this sentence level writing and provided specific feedback on that particular sentence. That way, students can confidently use these sentences as building blocks for a successful piece of extended writing!